What do we get by understanding what makes a room a room?

or: what’s the role of philosophical interrogation in disaster?

This is an edition of Questions You Have, special editions of the newsletter where I answer questions submitted by you, dear reader. Got a question? Drop it into this form: https://forms.gle/w88BLRFGRqpWDGtS9

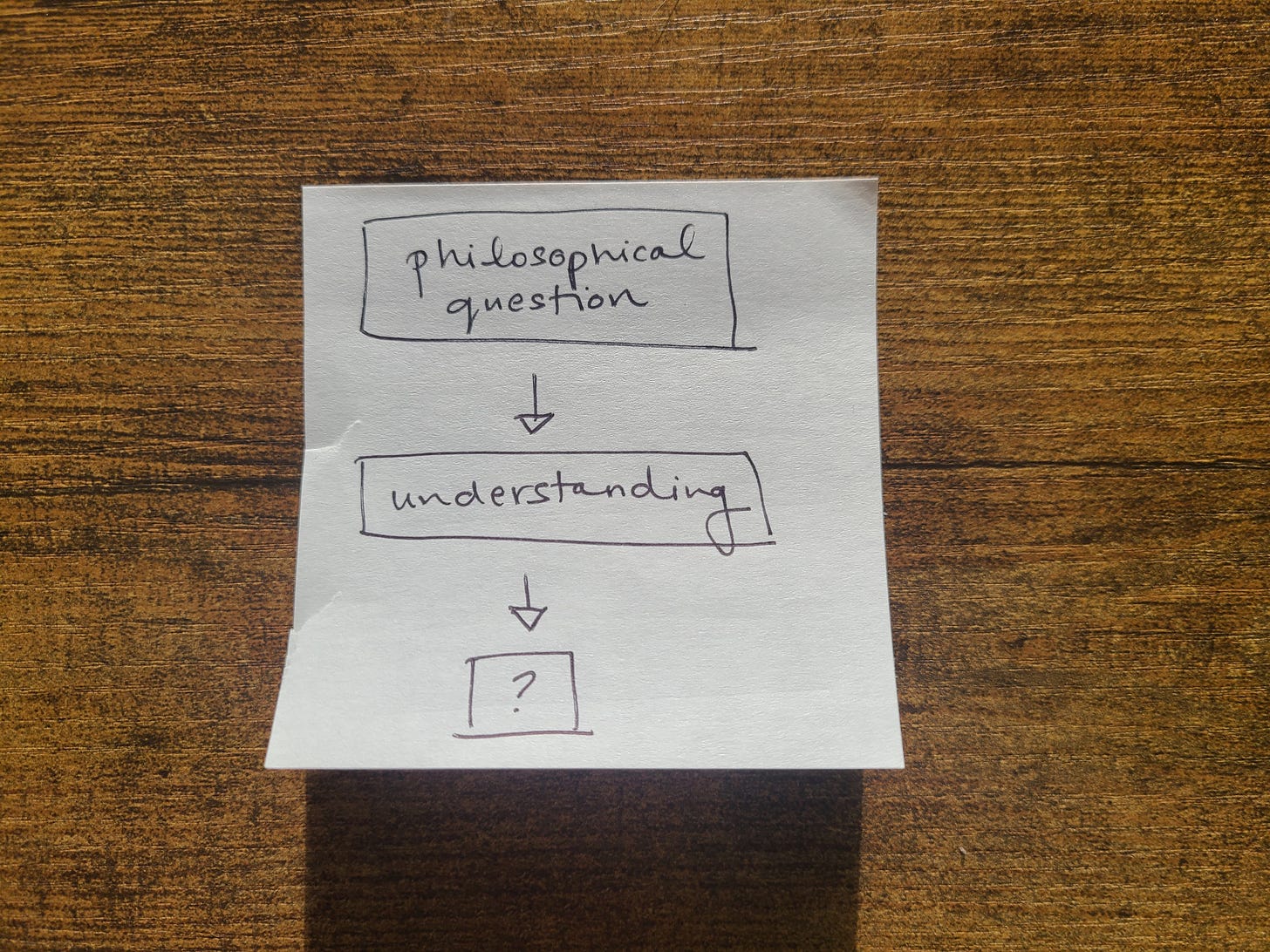

This question implies that understanding what makes a room a room isn’t the final destination but rather a stopping point on the way to something else. The “something else” is the thing we get. So what is that thing, the thing we unlock through understanding? I think another way of asking this question is, what is the point or purpose of understanding what makes a room a room? I think it’s like:

Paring this down to its most bare form, the potential answers to this question are:

Option 1. Something.

Option 2. Nothing.

To rule out option 2, all I have to show is that we get a single thing out of understanding what makes a room a room. I can’t speak for “we”, but I can speak for me, and I’m a part of the “we”, so if I get something, a portion of the “we” gets something.

— — — I’m feeling a physical discomfort as I attempt to write this, because I’m thinking about the fires burning through California. Of course. I feel completely ridiculous trying to write a philosophical rumination right now. What’s the point of thinking about Big Ideas when the Basics are crumbling and burning? I don’t know. But I guess, maybe that’s the question.

what’s the role of philosophical interrogation in disaster?

This isn’t the first disaster in human history and it certainly isn’t the last. I’m not the first philosopher (am I a philosopher? idk) and I’m certainly not the last. And the question of the point or purpose of philosophy certainly isn’t new, either.

Maybe I’m a try-hard, maybe I’m an optimist, maybe I’m totally delusional, but I do think philosophy serves a purpose, not just “even” in disaster, but perhaps “especially” in disaster.

My eighth grade History teacher used to say “Desperate times call for drastic measures.” He said this as a kind of neutral statement, like “drastic” was neither inherently positive or negative. I think he was trying to say that when times are or feel desperate, people crave big changes. Something’s gotta give.

We are in many ways living in desperate times. I don’t know if there was ever a time that wasn’t desperate, which I suppose brings into question just how “desperate” a time can be if all times are desperate. But that’s a question for another newsletter!

I see signs all around us that people are craving and executing drastic measures: Trump got elected again; Luigi Mangione; people are unionizing where they haven’t or haven’t been able to before; even reality TV has reached new levels of absurdity.

So what’s the role of philosophical interrogation in (a) the desperation and (b) the drastic measures?

Amid the desperation, philosophical interrogation can allow you to slow down and consider why you believe what you believe. Of course, there’s a time and a place for everything, including asking yourself the big questions. Only you know when that is; everyone has a different barometer.

If the desperateness of everything makes things feel faster, more frantic, more frenetic, then philosophy can make it feel slower, or at least that’s how it feels to me. Big questions are big because they can’t be answered quickly. They’re multi-layered and multi-dimensional, so attempting to address them requires nuance, which requires thought, which requires time. I mean this literally. Thinking about the big question takes time, time in which you are not doing other things, time in which you can look out a window, take deep breaths, feel the texture of the skin on your hands. Time in which you are here, for real, alive.

what makes a home a home?

what distinguishes object from memory?

how did we get here?

who is we?

The answers I arrive at when examining big questions don’t generally grant me joy (though they sometimes do, more often than I expect), but they do generally grant serenity. If I don’t arrive at a conclusion, I do arrive at an acceptance of the lack of conclusion, because I tried to find a conclusion, and didn’t find one, and that is, for better or for worse, a conclusion, too.

This feels like some kind of serenity. We need serenity amid disaster, however we can get it. A bath, a bath for your brain, a bath for your soul. Maybe you have five minutes, maybe you have 30 seconds — whatever it is, take it.

Amid the drastic measures, philosophical interrogation encourages you to clarify your values and stick to them. Drastic measures often catalyze knee-jerk reactions, of course! because they’re drastic! These measures are out of the ordinary, so of course we’re like, whoa! and we react accordingly.

Philosophical interrogation encourages a combination that I think is quite potent in the face of drastic measures: curiosity and critical thinking. Philosophical interrogation asks you to open your mind to questions you might’ve previously deemed unanswerable (and maybe they are). But it doesn’t stop there; it’s not enough to merely wonder. That’s not philosophical interrogation; that’s day-dreaming (also useful in its own way). Philosophical interrogation asks you to wonder, and then to posit an answer, and then to examine that answer from all angles. You might end up in the same place you started. You might end up in a different place from where you started. Either way, after rigorous philosophical interrogation, you will find yourself more confident in the perspective you’ve arrived at, whatever the fuck it is.

I think it is vital to own our values in all times, but again, perhaps “especially” in a time full of desperation and drastic-ness. More drastic measures are bound to come our way, and when they do, we need to remember who we are and who we want to be. We need to cleave to our values in the face of values being shoved down our throats. We need to cleave to our values in the face of fear, undue power, terror, and despair. Isn’t that when we need to understand and cleave to our values most?

If you don’t know what your values are, the only way you can live in alignment with them is through accident and happenstance, both of which are flimsy in the face of drastic measures enacted by people who do know and are all too ready to protect theirs.

what are my values?

what are your values?

These are questions with answers.

I guess I sort of did answer the question I originally set out to explore: what do we get by understanding what makes a room a room?

Something. We get something.